Expansion projects can create a great deal of excitement for a company. Whether the project is a new milk parlor, a hay barn, a silage pit or waste disposal system, these projects typically signify growth. While growth is exciting, it can also be a time of uncertainty. Large expansion projects generally come with large costs and questions of how those costs can be managed. In addition, they provide a number of tax planning and saving opportunities.

Reducing uncertainty

“How much will it cost?” may seem like a straightforward question. However, many times the typical response of, “Oh, we should be able to get it done for about (insert your number here),” leaves companies with even more questions when the project is done.

Typical questions heard at the end of unbudgeted and unmanaged projects include: “Why did it cost so much?” “Why didn’t we see this coming?” “What did we do wrong?” “How could we have saved money on the project?”

A simple way to avoid looking back with disappointment is through budgeting and cost analysis. Depending on the size and scope of the project, the initial budget could be as simple as a few line items put together by the company, or it could be an in-depth estimate broken down by major cost disciplines prepared by the selected contractor. Regardless of the form of the initial budget, it must be the starting point for a successful expansion.

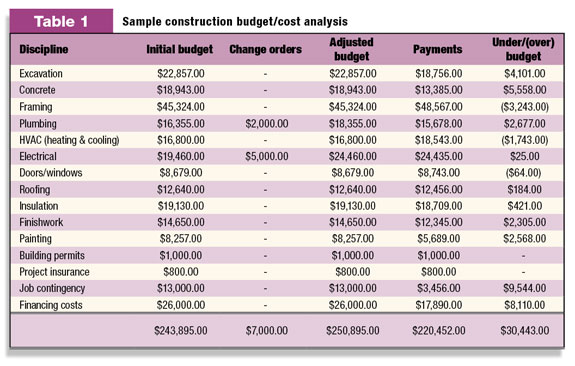

Table 1 shows a simple budgeting/cost analysis tool which can be utilized for projects. As seen in the tool, the information is broken down by line items based on major construction disciplines. While not every project will include all of these items, many of them will be present in most projects.

Special note should be given to the last four items: building permits, project insurance, job contingency and financing costs. These “soft” costs are often missed in the budgeting process and can lead to unexpected cost overruns.

With the initial budget in place, costs can now be better managed throughout the project. It is important to note that the initial budget is, as its name implies, a starting point.

There will inevitably be changes to the initial budget, whether they are intentional design changes or unexpected additional costs. Intentional changes are designated and tracked as “change orders” and should be quantified and approved before the additional work is done. Unexpected or unforeseen costs generally come out of the job contingency line item of the budget.

As payments are made for the completed work, each payment should be traced and accounted for in its appropriate line item. Managing the project in this way will allow potential overages to be identified early and allow adjustments to be made as needed to assure there are no unexpected overages once the project is completed.

Reaping potential tax rewards

An important consideration for large expansion projects is the recovery of tax benefits. In 2011 and 2012 there are three main approaches to asset recovery:

1. MACRS depreciation

2. Section 179 expensing

3. Bonus depreciation

Depending on a farm operation’s particular tax situation for the year, any one or all of these approaches may be applicable to smooth out tax brackets between years and save on total tax expense over the life of the expansion.

MACRS (modified accelerated cost recovery) used for income tax purposes will often be the recovery method of choice when a company’s income is in the lower tax brackets in the current year but is expected to be in a higher bracket in future years. The idea is to minimize the recovery of cost at low rates and maximize cost recovery in higher tax rate years, thereby maximizing the value of the tax deduction.

Internal Revenue Code section 179 expensing allows for the recovery of $500,000 in acquisition cost in the first year as long as no more than $2,000,000 in asset value is placed in service during the year. Section 179 is especially useful in a year when there is a spike in a company’s income and expensing asset purchases all in one year will help smooth out tax rates between years.

Section 179 is also useful in a year when a large dollar amount of fixed assets are placed in service in the last quarter of the year. When more than 40 percent of the total assets for the year are placed in service in the last quarter, a mid-quarter convention applies rather than a mid-year convention for MACRS depreciation – reducing the amount of depreciation deduction for the year.

Using Section 179 to expense the assets placed in service in the last quarter removes these assets from the mid-quarter test. Another benefit of expensing assets under Section 179 is that they receive the same treatment for regular and alternative minimum tax (AMT) purposes, therefore reducing the potential to be subject to AMT.

Bonus depreciation was implemented as part of the economic stimulus package. Generally, new assets with a MACRS life of 20 years and less purchased and placed in service after September 8, 2010, and by December 31, 2011, are eligible for 100 percent bonus depreciation. As farm assets have a MACRS life of 20 years or less, bonus depreciation is a great tool to be considered.

Unlike Section 179, bonus depreciation is not subject to a total asset purchase limitation. Like Section 179, it is treated the same for regular tax and AMT. If it is determined that writing off 100 percent of a group of assets would be detrimental to balancing tax brackets between years, an election must be made on the tax return to use either 50 percent bonus depreciation or MACRS depreciation for all assets with the same recovery life.

Assuming enough assets are purchased and placed in service during the year, Section 179 and bonus depreciation can be nicely coordinated to arrive at exactly the taxable income desired for 2011 and 2012.

Expansion projects are all about creating new ways for companies to capitalize on opportunities. A well-budgeted and managed expansion can reduce cost uncertainty and allow the company to reap the rewards of efficient new production capacity and opportunities for tax savings. PD

Co-author Brent Sandberg is an accounting consultant with the Logan, Utah-based accounting firm Jones Simpkins, P.C.

References omitted due to space but are available upon request to editor@progressivedairy.com .

Paul Campbell

Tax Officer

Jones Simkins, P.C.

pcampbell@jones-simkins.com