The major fatty acids (FA) fed to dairy cows are palmitic (C16:0), stearic (C18:0), oleic (C18:1), linoleic (C18:2) and linolenic (C18:3). The first two have been extensively reviewed in their individual and complementary effects.

When mixed together and then prilled, they provide the best nutritional package. More recently, oleic has been promoted by studies by one university laboratory as having unique benefits. How does that hold up under scrutiny?

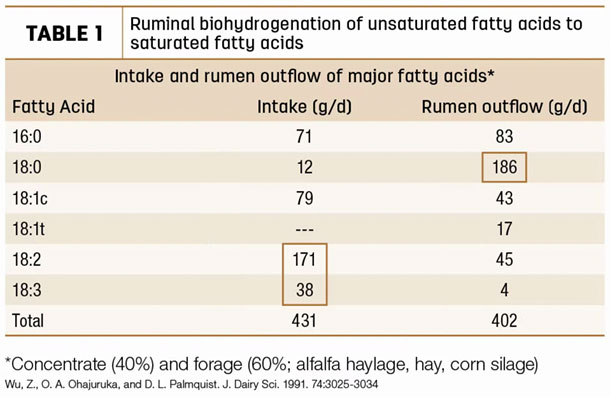

Let’s first digress a bit and address some components of fatty acid metabolism in dairy cows. A typical nonfat supplemented forage and grain dairy cow diet provides in this order fatty acids linoleic, oleic, palmitic, linolenic and stearic for a total of about a pound (431 grams) of dietary fatty acids as shown in Table 1. Note the disappearance of particularly linoleic (171 grams) and linolenic (38 grams) from intake to rumen outflow. That is because they are largely biohydrogenated in the rumen to stearic, which only comprised 12 grams from intake but increased to 186 grams in rumen outflow. So why not just feed more stearic instead of unsaturated fatty acids? That is a question we will come back to later.

A cow post-ruminally needs mostly stearic (two-thirds) and palmitic (one-third) fatty acids for its system. So the rumen microbes conveniently and symbiotically biohydrogenate (convert from unsaturated to saturated) fatty acids, which reduces their toxicity to rumen microbes and delivers mostly saturated fatty acids post-ruminally. And while about two-thirds of the saturated fatty acids in milkfat are stearic, the cow also needs stearic to convert to oleic. Thus somewhat axiomatically, the cow’s system eats mostly unsaturated fatty acids but needs mostly saturated fatty acids to meet its needs.

What happens when oleic fatty acid is fed to dairy cows? From the above study, you can see that considerable biohydrogenation occurred. More recent and extensive studies have estimated ruminal biohydrogenation of oleic to stearic ranges from 70% to 85%, with an average range then of 75% to 80%. So if you fed 60 grams oleic, for example, only 12 to 15 grams would survive the rumen. And if you tried to feed that much oleic, its lower melting point would make handling and use “greasy.” Cows do not like greasiness. But could a calcium salt then protect oleic from ruminal biohydrogenation? No, as an extensive review found that calcium salts do not really protect unsaturated fatty acids from ruminal biohydrogenation as approximately 15% of unsaturated fatty acids from calcium salts survived the rumen. Calcium salts dissociate in the rumen and release their fatty acids. If they did not, those unsaturated fatty acids could not be saturated in the rumen before they flowed out of the rumen. Formation of calcium salts also increases cost for this process and dilutes the fatty acids by the 12% to 15% addition of calcium to the calcium/fat mix.

But doesn’t milk get its oleic from the cow’s diet? Lipids leaving the rumen are 85% to 90% free fatty acids, two-thirds stearic and one-third palmitic, and 10% to 15% are phospholipids-microbial cell walls. Lipids in milk are about 65% saturated (40% palmitic, stearic, myristic) and 35% unsaturated (two-thirds oleic, linoleic, linolenic). The oleic in milkfat comes not from the diet but primarily from the mammary gland desaturating stearic to oleic. This is why the cow needs to convert dietary unsaturated 18-carbon fatty acids to stearic by ruminal biohydrogenation.

Doesn’t oleic increase neutral detergent fiber (NDF) and FA digestibility? This area of fatty acid potential impact on NDF digestibility is debatable and not corroborated by other research groups. There are questions about NDF and fatty acid assay methodology, possible modes of action, and only about 50% of the variation in NDF digestibility (R2 = 0.54) was accounted for by palmitic intake and NDF digestibility. We do not know for sure what accounts for the other 50% of that variation.

A recent study used midlactation cows for a 21-day period with the last five days used for data evaluation. There was no control diet, but diets contained a supplement with either 80% palmitic with 10% oleic or 60% palmitic with 30% oleic and included at 1.5% in diets. The ration was also atypical for midlactation cows containing only 45% forage from 24% corn silage, 18.9% haylage and 2.57% wheat straw along with 3.43% cottonseed. Given the ruminal biohydrogenation rate, the higher oleic diet would be equivalent to 60% palmitic, 22.5% stearic and 7.5% oleic. In this short-term study, there were no differences between the two diets in dry matter intake, dry matter and NDF digestibilities, and milk yield, but lower total fatty acid digestibility with the high palmitic treatment while milkfat percent was decreased with the lower palmitic treatment. The economics of these two fatty acid supplementations would have to be determined on a local basis.

Then what should I do with my lactating cow feeding program and supplementation with fat? Early lactation cows are the most responsive to fat supplementation, which does not decrease dry matter intake and aids in minimizing negative energy balance. I would supplement the high-production diet with about 1.5% fat to maximize its impact and benefits. Utilizing a lower level of fat supplementation across the whole herd I think is not very targeted, efficiently used and cost-effective. A palmitic/stearic fatty acid blend has been the most researched and reviewed. Based on recent research, high levels of either of these two fatty acids (greater than 80%) are most likely to have physical properties which would likely limit their digestibility. Thus, these fatty acids should first be blended together before prilling to eliminate this negative effect.

References omitted but are available upon request by sending an email to the editor.